So far, so good–second week of January and I’ve visited my second nature preserve toward my goal of visiting 50 this year. As many times as I’ve been to Sand Ridge Nature Center, I’d never gone five minutes further to Sand Ridge Nature Preserve. Today I did.

Along with Camp Shabbona Woods and Green Lake Woods, Sand Ridge Nature Center and Nature Preserve comprise a complex of protected lands measuring about one mile square. For the geography geeks among us, the federal Land Ordinance of 1785 created a system for mapping “western lands” (Illinois then was considered “the west”) for future development. Each township consisted of 36 sections, each section measured a square mile. That’s why, if you’re wondering, this particular nature complex is pretty much shaped like a square.

Along with Camp Shabbona Woods and Green Lake Woods, Sand Ridge Nature Center and Nature Preserve comprise a complex of protected lands measuring about one mile square. For the geography geeks among us, the federal Land Ordinance of 1785 created a system for mapping “western lands” (Illinois then was considered “the west”) for future development. Each township consisted of 36 sections, each section measured a square mile. That’s why, if you’re wondering, this particular nature complex is pretty much shaped like a square.

About 10,000 years before the Land Ordinance of 1785 was passed–for the geology geeks among us–Sand Ridge Nature Preserve was about 40 feet under the waters of Lake Chicago. As the waters retreated and advanced, and ultimately settled at their current Lake Michigan level, they left behind a series of beach ridges, alternating with low-lying lands. This “dune and swale” habitat was–and is–incredibly rich in the diversity of plants and animals it supports.

Most of the beach ridges were bulldozed, of course, and the low-lying lands filled in to make flat land for farming and development. However, the sandy soils were not that great for farming. So, in 1962, the Forest Preserved District of Cook County built a nature center on its section of former farm land. Three years later, in 1965, the Illinois Nature Preserves Commission dedicated the best of this land as its 9th dedicated nature preserve.

Unlike Sand Ridge Nature Center, there are no trails in Sand Ridge Nature Preserve. But that’s OK because what interested me most on my visit today was the utility corridor that runs alongside it. At first blush, you may not think there is much in common between a nature preserve and a utility corridor, but they share a powerful bond. As I point out in the book:

“The underlying strength of the Illinois Nature Preserves system lies in its being anchored in two powerful common law doctrines: dedication and public trust. According to common law, ‘a dedication is the deliberate commitment of land to a public use by the owner, with the clear intention that it be accepted and used for some public purpose.’ The doctrine of public trust dates back even further to Roman law and underpinned the tradition of the public commons in medieval European towns and the earliest towns in America. The doctrine, the essence of which is that the public has a legal right to certain lands and waters, is in evidence today in our nation’s innumerable parks, preserves, and public rights of way,” including utility corridors.

“The underlying strength of the Illinois Nature Preserves system lies in its being anchored in two powerful common law doctrines: dedication and public trust. According to common law, ‘a dedication is the deliberate commitment of land to a public use by the owner, with the clear intention that it be accepted and used for some public purpose.’ The doctrine of public trust dates back even further to Roman law and underpinned the tradition of the public commons in medieval European towns and the earliest towns in America. The doctrine, the essence of which is that the public has a legal right to certain lands and waters, is in evidence today in our nation’s innumerable parks, preserves, and public rights of way,” including utility corridors.

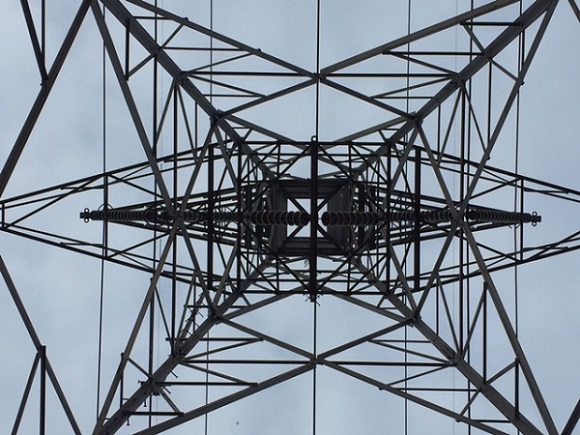

As you can see from this photograph, there is another powerful bond between nature preserves and utility corridors. Within the Chicago region, ComEd’s utility corridors encompass about 40,000 acres. That’s a lot of land. In fact, it rivals the 58,000 acres of dedicated nature preserve lands throughout the entire state of Illinois. For a number of years now, ComEd–in partnership with Chicago Botanic Garden, Prospect Heights Natural Resources Commission, and many others–manages its utility corridors using native plants. This helps buffer nearby nature preserves, expands habitat for rare and endangered species, such as Blanding’s turtles, and provides critical connections between our region’s nature preserves, forest preserve district lands and other natural areas.

Ever seeking to improve its natural areas program, this past year ComEd refined its mix of prairie grasses to help protect Illinois’ monarch butterflies. And in partnership with Openlands, ComEd annually provides grants to municipalities and park districts that focus on conservation, preservation and related open space improvements. In 2016, Our Green Region awarded 22 grants of $10,000 each.

Even on a cold, cold day, I love walking through Sand Ridge, with its icy swales reflecting the late afternoon sun, the crisp air occasionally punctuated with the “peep” of downy woodpeckers and the “eep” of a white-breasted nuthatch.

Even on a cold, cold day, I love walking through Sand Ridge, with its icy swales reflecting the late afternoon sun, the crisp air occasionally punctuated with the “peep” of downy woodpeckers and the “eep” of a white-breasted nuthatch.

But I also enjoy this walk for the beauty of the human interface. Certainly, we have destroyed most of our natural land–less than one-tenth of one percent remains. But here, in this place, I find beauty not only in the preserved land, but also in the engineering of a transmission tower, as well as in the commitment of a public utility–working with many different partners–to protect and buffer and care for our biological heritage, our remnant natural area gems.